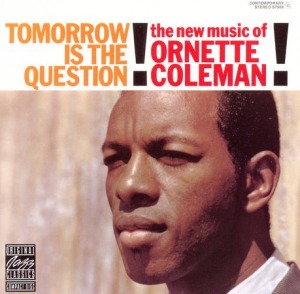

3. Ornette Coleman – Tomorrow Is the Question! LP – Contemporary, 1959 – $15 (RRRecords, 1/7)

I decided at the beginning of this year that the biggest remaining hurdle for my appreciation of jazz (don’t worry, I cringed typing that phrase just as much as you cringed reading it) is the nature of my listening. Instead of dabbling with a wide variety of performers and styles, I’ve opted to focus my efforts on a few key musicians I already know I like. Why I hadn’t done this earlier is beyond me—I can’t imagine thinking “I like 1990s DC rock, so I’m going to buy one album from each band and not worry about following up secondary material from favorites like Jawbox or Shudder to Think.” Such a process ignores understanding how an artist or band changes from album to album.

Ornette Coleman’s third album, The Shape of Jazz to Come, is one of the jazz albums that truly clicked for me on first listen, so it made sense to follow him down the rabbit hole. Tomorrow Is the Question! is Coleman’s second LP, trimming down his debut Something Else!!!! in both members and exclamation points. Gone is contractually obligated pianist Walter Norris, a notable departure of the chord foundation for Coleman’s trade-offs with Don Cherry’s cornet. The rhythm section temporarily dropped drummer Billy Higgins for Shelly Manne (who later appeared on Tom Waits’ Small Change and Foreign Affairs) and featured Percy Heath on bass for side A and Red Mitchell for side B.

These line-up changes underscore what I expected from Tomorrow Is the Question!: it’s a much more traditional album than The Shape of Jazz to Come. Traditional doesn’t necessarily mean bad—there are some lovely compositions on side A and the bright, optimistic mood is infectious—but it’s not as exciting as Coleman’s later works. Coleman and Cherry frequently hint at the free-jazz structures of Shape with their racing interactions, most notably on album highlight “Endless,” but the rhythm section, especially on side A, constricts this freedom. The liner notes mention Manne’s excitement to play without the usual boundaries, but he might have needed a few more albums to fully adapt to this style. There’s no other way to put it: the lack of Higgins and future Coleman standby Charlie Haden on bass is noticeable. I want songs to change course more often, to threaten to come completely apart.

Surely this line works its way into every review of the album given its title, but the most interesting aspects of Tomorrow Is the Question! are those that point to Ornette Coleman’s future recordings. It makes perfect sense that Coleman would progress somewhat gradually—if only two warm-up albums even qualify as gradual—into the free-jazz of The Shape of Jazz to Come. Perhaps the most astonishing fact is that Tomorrow and Shape were recorded two months apart in 1959 and released that same year. How many rock groups release multiple albums in the same year (Robert Pollard, sure) and display marked change from one to the next? (There goes Pollard’s furious hand-waving.) I’m certainly interested in seeing whether Coleman kept evolving at such a frantic pace.

4. Ornette Coleman – Science Fiction LP – Columbia, 1972 – $9 (RRRecords, 1/7)

I paired Tomorrow Is the Question! with Ornette Coleman’s 1972 LP Science Fiction in part to marvel at the expected juxtaposition. Unlike Tomorrow, which I correctly assumed would be a more traditional precursor to The Shape of Jazz to Come, I had no specific ideas of what Science Fiction would offer. Between the hazy, spooky cover art and the decidedly out-there album title, Science Fiction could’ve blasted Coleman off to Sun Ra’s lost planet of space-jazz, taken root in Miles Davis’ jazz-fusion, or found its home with Herbie Hancock’s jazz-funk. I wouldn’t have been surprised by any of these outcomes, yet none of them is remotely accurate.

A look at the personnel would’ve grounded my expectations. Yes, two songs feature vocals from Indian-born singer Asha Puthuli and one features spoken word from poet David Henderson, but regular Coleman contributors like Don Cherry, bassist Charlie Haden, and drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins appear on every track. Science Fiction is never too far from the free-jazz I’m used to hearing from Coleman, but it’s how specific songs and performers stand apart from this foundation that’s intoxicatingly great.

Asha Puthuli’s soulful vocals on “What Reason Could I Give” and “All My Life” are superb. Her voice intertwines with Coleman and the other horns on each song, pulling off the trick marvelously on “All My Life.” Billy Higgins sounds like a man possessed drumming on “Civilization Day.” Charlie Haden’s jaw-dropping solos in “Street Woman” and “Law Years” find tones and textures beyond the usual fingerboard workouts, sounding almost like drones during the former song. Poet David Henderson’s contribution to the title track couples with swarming horns and a baby crying for a profoundly bizarre listening experience. “Rock the Clock” adds texture from Coleman’s violin and Dewey Redman’s musette, which I assume is what sounds like a wheezing electric organ. “The Jungle Is a Skyscraper” lets Coleman, trumpeter Bobby Bradford, and tenor saxophonist Redman take center stage with their solos. There simply isn’t a song on Science Fiction that fails to grab my attention.

Science Fiction is an album I’ll need to spend more time with in order to properly digest. My lone critique of it now is that because of the shifting line-ups, it feels scattershot from song to song. I could have easily done with an album of Asha Puthuli vocals, an album of crazed solos from Billy Higgins and Charlie Haden, or an album of tripled solos from Coleman, Dewey Redman, and Bobby Bradford. Getting all three, in addition to the usually sparkling contributions from Don Cherry and the bizarre poetry of the title track, is a blessing and a curse. Ten listens down the line, perhaps it’s more of one than the other.

|

|

I first visited RRRecords when my friends Howard and Scott invited me on a trip up to Lowell to visit the store and see the nearby Jack Kerouac exhibit, which displayed the original scroll of On the Road. I learned a few lessons about RRRecords during that first visit: one, always call ahead to make sure Ron is there and that the store is open; two, no, really, call ahead with a specific time; three, it’s a haven for noise music; and four, bring cash. We ended up wandering around Lowell because we visited during Ron’s lunch hour, but once we got in the store I immediately wished I’d brought more cash. Even without a penchant for noise music there was more than enough for me to get excited about—if memory serves, I picked up a long-desired 2LP copy of Dirty Three’s Ocean Songs and $4.50 copies of David Bowie’s Low and the Smiths’ Meat Is Murder. While this trip wasn’t quite as astonishing of a deal, five solid LPs for $35 total is worth a visit to Lowell.

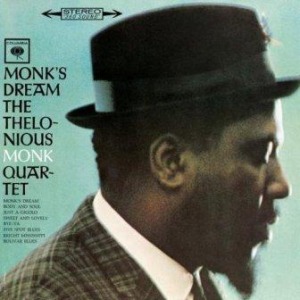

101. Thelonious Monk – Monk’s Dream LP – Columbia, 1963 – $8

I went up to RRRecords with the intent to purchase at least one jazz album, whether original or reissue, since the stock is usually good and reasonably priced. This in-shrink reissue of Monk’s Dream was a mere $8, a few bucks cheaper than any of the jazz selections at Newbury Comics. I only had one Thelonious Monk LP in my collection, a worn copy of Monk in France from a dollar bin, and he seemed like a worthy candidate for expansion. His piano style isn’t flashy, rather insistently idiosyncratic, veering off in unexpected melodies without losing track of a song. A few of the keywords from the sleeve notes are “fun” and “humor”; there’s a welcome lightness to Monk. It’s excellent background music, but particular elements reward closer attention, like the percussive trills near the end of “Sweet and Lovely.” Monk is also a remarkably deferential bandleader, letting tenor sax player Charles Rouse take the lead on the title track.

I have to note that Monk’s Dream, his first LP for Columbia, primarily features music that he had previously recorded and released on other labels. Given that other jazz luminaries like Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman, and John Coltrane were focused on releasing all-new material, pushing themselves further with each set, it’s a bit of a disappointment that Monk’s Dream is a mid-career best-of (best certainly applies; nothing here feels unnecessary), but perhaps Monk was fine with progressing his style on existing material. It’s a strange concept for someone so ensconced in rock music, but standards were kept fresh in jazz for a reason.

102. Terry Riley – A Rainbow in Curved Air LP – Columbia, 1967 – $8

In my seemingly endless search for Steve Reich LPs, I may have ignored his peer in minimalist music, Terry Riley. Reich, Riley, and Philip Glass form the triumvirate of contemporary composers associated with the minimalist movement in the public eye, although Glass has attempted to distance himself from its trappings. I own one other Terry Riley album, The Harp of New Albion, a solo piano endeavor from 1986 that explores the possibilities of just intonation, but A Rainbow in Curved Air carries more historical renown, second only to In C in his catalog. Rainbow is certainly more striking than Harp, sounding like a colony of bees swarming around a piano. The title track’s rolling, shifting synthesizer lines inspired Pete Townshend’s parts in The Who’s “Won’t Get Fooled Again” and “Baba O’Riley” (note the titular reference), but I prefer the less pointed instrumentation (organ, saxophone, tape loops) on the other piece, “Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band.” “Poppy Nogood” was originally performed in a six-hour concert and later released in a somewhat longer version, but the twenty-one minutes here are trance-inducing. Both compositions remind me of Reich’s later Music for 18 Musicians, but with more emphasis on improvising the recurring patterns.

I suspect various factors contributed to Glass and Reich overtaking Riley in terms of popular appeal—the former collaborates with pop stars and scores films, the latter’s works are both dense and short enough to be perfect for album-length recordings and frequently touch upon political and cultural unrest—but overlooking Riley isn’t a mistake I’ll make again. First, however, I’ll have to find out which recordings come most recommended, something that’s never been an issue for Reich’s catalog. Starting with A Rainbow in Curved Air would’ve been a wise decision.

103. Sonic Youth – Rather Ripped LP – Geffen, 2006 – $5

Sonic Youth forms the musical backbone for many indie/alternative guitar-rockers, but they’ve never attained that status for me. I’ve logged countless hours with Daydream Nation and lesser amounts of time with Sister, Goo, Dirty, and Washing Machine, with smatterings of their other records, but I’ve never counted them as one of my favorite groups, never rushed out to buy their new album, never seen them live. The last admission might be the most startling, but I don’t recall them playing Champaign during my college years, and I had to be excited about a band to make the drive up to Chicago. It's possible that seeing them live would do it, but their shows aren't exactly bargain priced.

Here are four logical points when I could’ve gained that level of excitement for Sonic Youth: 1. The group appears on The State’s CBS special, performing a truncated version of “The Diamond Sea.” It’s beautiful in an unfamiliar way and completely unexpected for network TV. 2. I get a copy of Daydream Nation from Columbia House and hear “Teenage Riot” for the first time. It’s an awesome song, but I get stuck on it and don’t absorb the rest of the album for a while. 3. A high school classmate does a presentation on the group in senior year public speaking, playing parts of their earlier works (which I did not care for at the time) and their more recent work. I wasn’t friends with the guy, which is baffling to me now. 4. I read (and reread) Michael Azerrad’s Our Band Could Be Your Life, which prompted investigations or re-investigations into groups like Minor Threat, Fugazi, Misson of Burma, Dinosaur Jr., the Replacements, and Minutemen. All of these moments should’ve spoken more to me, should’ve pushed Sonic Youth up higher in my personal musical hierarchy, but didn’t quite do it. I gained an appreciation for Sonic Youth, but not a love.

So what stopped it from happening? Here are my six best guesses: 1. The members of Sonic Youth always seemed too cool for me, especially when they hosted 120 Minutes. That show introduced me to groups like Jawbox, Girls Against Boys, and Shudder to Think, but I suspect that either strange songs, weird personalities, or terrible videos delayed my fondness for later favorites. (Stereolab, I am looking at you.) Thurston and company appeared on the show with an aloofness that was a fuck off to anyone who didn’t care and a fist pump for those who did. Stuck in between, I didn’t know how to respond. 2. Speaking of too cool for their own good, Kim Gordon’s vocals annoy me 75% of the time. I do not feel alone in this sentiment. What I wouldn’t give to trade some of these songs for Lee Ranaldo vocals. 3. I should’ve heard Goo or Sister after Daydream Nation, not Washing Machine. 4. Given how important Sonic Youth were to 1980s independent rock and how much they evolved (no pun intended) during that decade, it would’ve been a lot more exciting to follow them then. 5. Sonic Youth’s vocals and lyrics often emphasize their art-scene detachment over the emotional undercurrent of many of my personal favorites. 6. As much as I respect them for constantly changing their approach, it causes them to often ignore their strengths in favor of noisy indulgences or unnecessary tangents. That I am complaining about tangents regarding Sonic Youth should be a huge sign that I’m probably never going to “get” them in the way that some friends of mine do. (Hello, Joe Martin.)

At this point I’m happy sticking with Daydream Nation, Sister, and Goo, with specific songs from the other albums (I almost forgot about their DVD, which is actually quite enjoyable throughout) and an occasional spin of SYR1: Anagrama, no longer forcing the issue with the group as a whole. Yet I’ve still picked up two cheap LP copies of Sonic Youth albums from RRRecords, first A Thousand Leaves last year, now Rather Ripped. Is it the value? Is it the lingering hope that one of these albums will click? Who knows. Like almost all of their recent records, Rather Ripped was lavished with praise upon its release, meaning that I had to dutifully ignore recommendations from friends to check it out ASAP. I’ll take my sweet time, thanks.

On the surface, Rather Ripped is a marked change of pace, filled with tidy track times and focused songwriting. There’s still plenty of trademark left turns to be found, but in general, they close out their stay on Geffen with an atypically approachable album. The first three tracks are great, Moore’s “Incinerate” in particular, but “Sleepin Around” and “What a Waste” have grating hooks that I’d love to pull from my brain. The rest of the record is solid, if not quite mind-blowing. The main problem is ironic, given issue #5 above. Usually I want less fucking around from Sonic Youth, this time I wanted more. Trim a few annoying songs, spread out more on a few of the good ones, and it’s a noticeably better album. As is, it was worth the $5 and will likely get more spins than A Thousand Leaves.

104. Archers of Loaf – All the Nations Airports LP – Alias, 1996 – $8

I had my choice of Archers of Loaf’s All the Nations Airports and Girls Against Boys’ Cruise Yourself for my classic 1990s indie rock double dip purchase. Airports isn’t the picture disc edition and Cruise Yourself wasn’t the first pressing with the “Red Bar” single, so I opted for the album not missing any bonus tracks. It’s all about the music, see.

Aside from the completely superb Vs. The Greatest of All Time EP, it’s been quite a while since I’ve listened to an Archers of Loaf album in full thanks to my 24-track best of compilation, Calling Out the A&R. Don’t view this habit as an indictment of the group’s albums—there are plenty of great tracks missing from my compilation, many of which I’ve seen on “competing” attempts to condense the Archers’ brilliance into a single disc—but like Pavement (and, to a lesser extent, Polvo, both of whom have earned similar compilations), AOL has such tremendous highlights that it’s impossible not to focus on classics like “Web in Front,” “The Lowest Part Is Free,” “Harnessed in Slums,” “Scenic Pastures,” and “Fashion Bleeds.”

So what about their albums? Icky Mettle’s penchant for lo-fi noise turns some away, but it’s hard to top its combination of raw, spontaneous energy and polished hooks. Eric Bachmann commented directly on this energy in a 2005 interview—“When we first came out we had that energy. It's a weird thing that you can't put your finger on...I listened to Icky Mettle, and I almost cringe when I hear it.” I suspect he’s particularly embarrassed by amorphous moments like “Toast,” but I’ll gladly accept such indulgences if it gets me the oblique pop of “Web in Front” and the noisy intensity of “Backwash” in return. Vs. the Greatest of All Time is a tidier five songs and seventeen minutes, but those five songs are all stand-outs. (If only they’d included the tighter version of “Revenge” from The Speed of Cattle with two fewer minutes of spaghetti western noodling.) Vee Vee makes a jump in fidelity and structure without losing inspiration or bite, but I tend to lose focus during the second side. Airports, their first album with major label distribution, holds together better than any of their other releases, but doesn’t quite hit the highs of its predecessors. The rarities compilation The Speed of Cattle is among the finest of its kind, featuring plenty of glorious b-sides and a few superior alternate takes of album tracks. White Trash Heroes, their 1998 swan song, is more commendable than many other final statements from 1990s indie rockers (cough, Shapes, cough, Terror Twilight) because of its stern adherence to exploring new stylistic territory, but only half of the album’s songs are actually good. Only White Trash Heroes and The Speed of Cattle encourage a best-of compilation, but Icky Mettle and Vee Vee certainly look better through the rose-colored glasses of their strongest songs.

Returning to All the Nations Airports on vinyl makes sense, since it’s defined by how the pieces fit together. Putting the arrival and departure times on the back of the albums for each song, including the length of the pause between them, isn’t just a mark of aesthetic consistency—it’s a huge tell for the importance of the album’s sequencing. The brief “Strangled by the Stereo Wire” ends abruptly and then jumps into the title track like a well-rehearsed trick of their live set. “Worst Defense” blurs into “Attack of the Killer Bees.” The absorbing piano ballad “Chumming the Ocean” is an absolutely perfect closer for side A, necessitating a brief pause before you flip the LP over. There’s a noticeable pause between the western-informed instrumental “Bumpo” and the introspective churning of “Form and File.” Sandwiching the desperation of “Distance Comes in Droves” with a pair of instrumentals, “Acromegaly” and “Bombs Away,” ends the LP on a high note. Thanks to this superb sequencing (and the strength of the individual songs), Airports turns potentially token elements like the piano ballad and the transitional instrumentals into the standouts.

Airports’ strengths—consistency and sequencing—are at odds with the best-of approach, which might have lowered the album’s status when viewed through the lens of my compilation. That doesn’t excuse the lack of a “Harnessed in Slums” (“Chumming the Oceans” equals its quality but not its tempo), but it certainly makes the double dip more rewarding than the usual “But it has bigger artwork!” rhetoric.

105. Volcano Suns – Thing of Beauty 2LP – SST, 1989 – $6

Even after catching up with All Night Lotus Party with Record Collection Reconciliation, I still have an unplayed Volcano Suns album in my collection (Bright Orange Years), but I decided to pick up Thing of Beauty anyway. I often see Volcano Suns at Looney Tunes for $15 or $20 (as I’ve mentioned before, Peter Prescott used to work at their Cambridge location), so finding a double album for $6 seemed like a steal.

There’s no doubt that Thing of Beauty is a double album. There are stray tracks like the meandering “No Place” and the fourth side is padded with an enthusiastic cover of Brian Eno’s “Needle in the Camel’s Eye” and the CD pressing adds MC5’s “Kick Out the Jams” and Devo’s “Red-Eye Express.” (Tangent: I wouldn’t mind if 2LP sets with the fourth side left blank added b-sides or bonus covers; just leave them unmarked on the sleeve. Why waste the vinyl?) On the whole, Thing of Beauty is more melodic, less aggressive than All Night Lotus Party, but it’s not a drastic reversal. It’s also noticeably more democratic than ANLP, letting bassist Bob Weston (producer for Rodan’s Rusty and Shellac bassist) and new guitarist David Kleiler write and sing their fair share of songs, which adds different voices and pads the runtime. It’s strange that drummer/vocalist Peter Prescott is the lone remaining member from their first incarnation, but one spin of the brawny Mission of Burma-esque opener “Barricade” suggests that he had the rights to that brand of post-punk. If Thing of Beauty had twelve strong tracks instead of twenty, I’d put it on again in a heartbeat, but it’s begging for a reprogrammed track listing.

|

|

Stereo Jack’s could’ve easily made a few appearances on this list (always coinciding with a trip to the nearby Boca Grande for a beef birria burrito), but on most visits I come out empty-handed. If I were more knowledgeable on jazz, perhaps that wouldn’t be the case, since their just-in bin is dominated by jazz and classic rock. I occasionally found a keeper in their stacks (Spinal Tap LP, Rex’s Rex for a few bucks, a Cocteau Twins LP) and today the winner was a copy of Boys Life’s Departure and Landfalls. Five bucks is a steal, but it also brought up the whole “Ten dollar minimum for credit purchases” issue, so without any cash on me, I opted to buy some cheap filler rather than venture off to an ATM. I searched through almost every LP in the hopes of finding a $5 LP I wanted to hear, but the highlights of the rock vinyl were things I already own (Colin Newman’s A-Z, Brian Eno’s Music for Films, L’altra’s Music for a Sinking Occasion), the jazz highlights were more expensive, and the seven-inches were overpriced, so I grabbed two cheap bin CDs and an Oscar Peterson LP for my wife.

97. Boys Life – Departures and Landfalls LP – Headhunter, 1996 – $5

Boys Life is one of the few Midwestern rock staples that I never got into, despite being highly praised by everyone else remotely interested in the scene. Why the delay? One pragmatic reason and one kneejerk reason: I simply didn’t run into their albums in stores and I associated them with the irritating bits of Crank! emo that I’d heard. The former issue has since been resolved by Mystery Train and Stereo Jack’s, respectively. That latter aspect is hard to admit in retrospect, but Brandon Butler’s vocals are the weakest part of Boys Life, which is par for the Crank! course. I fully expect people to call me out on this point, but think of it this way: how many bands sing like this nowadays? It’s all mid-1990s emo vocals, which involves mumbled verses (Soo-young Park style), surprisingly melodic choruses, and straining bridges. If I’d heard Departures and Landfalls in 1996, maybe I’d ignore this aspect or even cherish it as genuinely emotional (which, I suppose, it still is), but it’s not like I can go back to Hum’s Electra 2000 and not cringe when Matt Talbott reaches for notes on “Scraper.” The reality is that neither vocalist is consistently poor, nor do they ruin the otherwise excellent music on their respective albums, but there’s a reason why they kept getting better at singing on future records. Anyway.

Departures and Landfalls didn’t fully sink in until I gave it a focused listen with headphones. The first two songs, “Fire Engine Red” and “All the Negatives,” are up-tempo rockers with jittery nerves and jagged chords, but from there Boys Life spreads out and embodies the space that the Midwest has to offer. C-Clamp is my go-to band for picturing the drive through Illinois cornfields on I-57 from Chicago to Champaign, but that image has a specific time stamp. The golden guitar tones of Meander and Return work best along with a sunset, but the periodic growl of Boys Life’s guitars fit with a late evening drive. “Twenty Four of Twenty Five,” “Radio Towers,” and “Painted Smiles” all stretch out in quiet, determined ways, building toward an eventual explosion of light and then a gradual darkening. Bob Weston’s production is perfect for this record, giving it the necessary dynamic range to capture both ends of this spectrum. Weston fills Departures with nice touches like the ghostly echoing drums on “Sleeping off Summer,” the crickets in “Painted Smiles,” and his own trumpet on the same track. Butler’s vocals work best on these dynamic tracks, since he’s not forced to yelp over churning guitars. When he sings “Let me out of here today” on “Sleeping off Summer,” it’s a perfect blend of resignation and pleading. Departures and Landfalls didn’t grab me as quickly as I thought it would, but there’s no debating whether its placement in 1990s Midwestern rock is deserved.

Side note: I just noticed that Boys Life frontman Brandon Butler went onto form Canyon, a DC-area rock group whose self-titled debut was one of the CDs I reviewed back in my Signal Drench days. Furthermore, that record featured John Wall, the drummer from Kerosene 454 who kicked ungodly amounts of ass in that group. Butler was also in the Farewell Bend, a group who shared a split single with Shiner on DeSoto. I should probably unearth Canyon and track down that Farewell Bend full-length, huh?

98. Oscar Peterson Trio – Tristeza on Piano LP – MPS, 1972 – $2

When I met my wife during our freshman year of college, she had a fairly small binder of CDs. It was a mix of alternative rock she’d gleaned from Chicago radio, jazz that she’d heard from her parents and grandparents, and a few older favorites like the Beatles. She wasn’t as obsessed with music as I was/am, but she was intrigued by the existence of thousands of other bands that she’d never heard of, which was a huge step up from the usual scoffing of my high school classmates. That started my “I think you’d like this band, even if they’re not exactly my favorites” habit, which I believe started with the Get-up Kids. I’ve since learned to be far more careful with this habit, since there’s only so much feminine indie folk I can take at a given time. Fortunately I’ve found a reasonably large middle group in our tastes, usually encompassing non-aggressive indie rock, post-rock, and electronic music, while excluding hip-hop and metal. (She just confirmed this divide.)

I do think of my wife’s tastes when I’m out record shopping, however, and I picked this album up because of my wife’s fondness for Oscar Peterson, not knowing much about Peterson’s career arc. (If it had been an album called Oscar Peterson Trio by the post-rock group Tristeza, I would have been far better prepared.) My wife’s tastes in jazz differ heavily from mine; she doesn’t share my growing fondness for free jazz or fusion, instead preferring Peterson, Milt Jackson/the Modern Jazz Quartet, and other pianists like Thelonious Monk and Ahmad Jamal, Monk being a nice point of convergence.

I held off on listening to Tristeza on Piano until she was listening and could share some of her feelings on the album. From the first few paragraphs of the liner notes discussing the Brazilian flavor of the title track, I expected something different, but “Tristeza” is actually ridiculously fast jazz piano. I coined it “speed jazz,” which my wife viewed as a slight to Peterson’s technical prowess, which is pushed to its limits on that song and “Nightingale,” the only song on here that he composed. “Nightingale” does have some more typical Brazilian percussion, but both songs are driven by Peterson’s blazing hands. My wife was particularly impressed by his accuracy in these songs, since neither comes off as too fast or sloppy in the least. This style pops up occasionally during the rest of the album, but later songs like Gershwin’s “Porgy” and Jobim’s “Triste” have a more familiar pacing to what I’d heard from Peterson. My wife was impressed by both styles, but when pressed, she admitted that she preferred the more soulful style on the slower tracks, and I’ll agree with her on that point. I would’ve liked another original composition or two on the LP, but my wife was fine with hearing his rendition of “Fly Me to the Moon.” All told, she enjoyed Tristeza on Piano but wasn’t floored by it, and I think I’m in a similar state. Well worth the two bucks, at least.

I hadn’t noticed this before listening to the album, but Wikipedia notes that Tristeza on Piano was Peterson’s “eulogy of the recently deceased Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin, the Monterey Pop Festival stars.” I have a hard time processing exactly how it eulogizes them—the accelerated technical prowess of “Tristeza” and “Nightingale” certainly impress like Hendrix’s solos, but there’s no mention of it in the liner notes and nothing in the music itself that felt mournful.

99. Medicine – Shot Forth Self Living CD – Def American, 1992 – $2

I picked up this CD because of its constant mentions in “underrated shoegaze albums” discussions and it certainly delivers on my expectations. Female and male vocals, loads of gauzy guitar feedback, periodic bursts of white noise, some stretched-out compositions (the opener “One More” and the closer “Christmas Song” each go past eight-and-a-half minutes), and sweet pop hooks floating through the mist: calling Medicine a Los Angeles version of My Bloody Valentine isn’t far off. Those long tracks are the highlight, but the short, seemingly radio-friendly “Sweet Explosion” and “Defective” probably got them signed. I suspect that fellow Californians the Lassie Foundation hold this album dear, since a number of these guitar sounds recall moments from that group’s excellent 1999 album, Pacifico, minus the Lassie Foundation’s twee inklings, of course. Shot Forth Self Living is too structured to be pure shoegaze and too woozy to be stock 1990s alternative, but the drifting middle-ground between the two genres makes for an intriguing listen.

I’m tempted to scan in the artwork and annotate every facet of the art that’s typical to early 1990s major-label cut-out alternative rock. There’s the vague cover art, likely a negative of a photo of their favorite bar. There’s a colorized panel of a playground with an overlay of unconnected photos. There’s little consistency in terms of a color scheme. Even the all-caps font for most of the text (like they’d only use one font!) seems stereotypical to the era. My preference for vinyl is quite apparent, but the three-panel art of Shot Forth Self Living must’ve been designed with the confines of the compact disc in mind.

100. Versus – Two Cents Plus Tax CD – Caroline, 1998 – $2

Versus recently played a reunion show in Boston with a guest appearance from Unrest frontman Mark Robinson, but I passed on attending. While I enjoy the fuzzy indie rock of 1994’s The Stars Are Insane and parts of the more polished, but less compelling Secret Swingers (specifically “Lose That Dress,” “Glitter of Love,” and “Ghost Story”), Versus lost my interest as they gained fidelity. I’d heard a few songs from Two Cents Plus Tax early in the file-sharing era and enjoyed “Radar Follows You,” lazy rhyming and all (a consistent problem for Versus lyrics), but I missed the dynamics of “B-9” (which I first heard on the soundtrack to Half-Cocked, a fine indie-rock compilation) and the lilting pop of “Circle” and “Blade of Grass.” By the time of their 1999-2000 stint on Merge, I felt like they’d outstayed their welcome, especially given the number of 1990s indie rock bands who split around that time: Pavement, Archers of Loaf, Polvo, Seam, etc. Perhaps as penance for my MP3 of “Radar Follows You,” I grabbed this cheap copy of Two Cents Plus Tax for two bucks plus tax, hoping that I’d given the group enough time to sound fresh, but unfortunately it’s pretty much what I expected. At the very least it reminded me to give The Stars Are Insane a few spins in late summer, since it’s tailor-made for that season.

|

46. Herbie Hancock – “Autodrive” b/w “Chameleon” - CBS, 1983

Why I Bought It: I’m primarily familiar with Herbie Hancock’s early 1970s albums Head Hunters and Thrust, which are eminently regarded, highly enjoyable jazz fusion albums with completely amazing album covers. This 12-inch single features one song from Hancock’s 1983 electro-jazz album Future Shock and a remix of “Chameleon” from Head Hunters, bridging the gap between these two eras. I’m wary of the concept of electro-jazz, especially given my discussion of dated 1980s production techniques in my last post about the Art of Noise, but it’s entirely possible that Hancock could avoid those stumbles.

Verdict: Herbie Hancock is not kidding with this electro-jazz concept. Between the sampled shouts, the constant laser gun blasts, and the tinny electronic drum kit, he’s loaded “Autodrive” with enough 1980s production clichés to make Wang Chung jealous. Sure, a grand piano makes an appearance to remind listeners of Hancock’s roots, but I can understand why “Rockit” from Future Shock was an MTV success; this song sounds like early 1980s MTV new wave. Hancock clearly has fun with these tropes, so even though the individual sounds have aged poorly, the song still has a playful, light air that almost encourages such aging. As for the flip side, I’ll have to consult the Head Hunters version to confirm this suspicion, but the remix of “Chameleon” doesn’t seem drastically different. The comparative subtlety of this track works well, since adding sampled shouts to bring an older piece up to date would have been comical instead of inspired, but it’s ultimately unlikely to steer me away from Head Hunters and toward Future Shock.

47. Unwound - New Plastic Ideas - Kill Rock Stars, 1994

Why I Bought It: I first encountered Unwound’s brand of Sonic Youth–informed punk rock with either “Dragnalus” on the soundtrack to Half-Cocked or their 1996 LP Repetition, but I’ve primarily stuck with Repetition and the relative bookends of their output (barring their self-titled debut), 1993’s abrasive Fake Train and their 2001 swansong double album Leaves Turn Inside You. Unwound’s signature aggressive detachment, honed to a cool perfection on “Corpse Pose,” pulls me in and keeps me at bay. With few exceptions—the lovely “Lady Elect,” the aching “October All Over”—my relationship with Unwound is one of respect, not affection. But including their 1998 LP Challenge for a Civilized Society in a round of iPod Chicanery underscored their almost clinical level of effectiveness when they’re on, which in the case of Challenge is about fifty percent, which opened me up to grabbing one of their other albums.

Verdict: New Plastic Ideas strikes a welcome balance between the unhinged Fake Train and the machine-like efficiency of Repetition. Although the album lacks the polish of Repetition and the explorative nerve of Leaves Turn Inside You, there’s a refreshing consistency to these nine songs their later records sacrificed in the favor of ruthless experimentation. The restrained aggression of the lengthy instrumental “Abstraktions,” the mock-yearning of “Envelope,” and the dynamic peaks of “Arboretum” stand out, but each of the songs merits a mention. I need to listen to Leaves Turn Inside You again, but it’s entirely possible that New Plastic Ideals vaulted to the position of my favorite Unwound release with one listen.

48. Mekons - So Good It Hurts - Cooking Vinyl, 1988

Why I Bought It: When I purchased So Good It Hurts a year ago I only had vague notions of the Mekons’ alt-country, informed primarily by Touch & Go Records catalogs. After checking out the esteemed Fear & Whiskey and Mekons Rock ‘n’ Roll in my continuing efforts to expand my base of 1980s independent rock, it’s time to stop putting off listening to this album.

Verdict: My decision to hold off on listening to So Good It Hurts until I’d heard more typical Mekons records looks smart in retrospect. So Good It Hurts starts off auspiciously with the reggae-inflected “I’m Not Here (1967)” and incorporates more reggae, Cajun, and Celtic influences than expected. While it’s still a relatively solid album, such quasi-imperialist exploration deemphasizes the songwriting, leaving a few of the tracks to survive on egalitarian slogans. The title-citing “Fantastic Voyage” and the Sally Timms– sung “Dora” and “Heart of Stone” are the primary highlights, with the latter song sounding like a revitalized standard. So Good It Hurts could be a grower, but for now I’d like to focus on the Mekons’ alt-country efforts.

49. Count Basie - Basie Land - Verve, 1963

Why I Bought It: It’s a jazz record from the early 1960s released by Verve, I figured my wife, whose jazz preferences usually run closer to Oscar Peterson and Milt Jackson, would enjoy it, and it cost me all of $1.05. Naturally, I choose to listen to it when my wife is out of town.

Verdict: As someone who’s primarily delved into bop and fusion, Count Basie’s enthusiastic brand of swing jazz is a significant change of pace. The title track opens the LP with a big band–¬level of energy and “a cookin’ solo by tenorman Frank Foster,” but I prefer the slower pacing of the three tracks that follow it. “Instant Blues” is an apt title for the final song on side A. Most of side B returns to the pace of “Basie Land.” Basie Land is a nice diversion, but I doubt that big band/swing jazz is likely to gain a formidable presence in my record collection.

50. Gang of Four - Songs of the Free - Warner, 1982

Why I Bought It: When I finally bought Gang of Four’s classic Entertainment! I also picked up their next two albums, Solid Gold and Songs of the Free, not anticipating that their debut would refuse to budge from my turntable. From “Ether” to “Anthrax,” Entertainment!’s combination of minimal, razor-wire guitar phrases, funk- and dub-inspired bass lines, and Jon King’s remarkably catchy Marxist critique of British culture qualifies it with Wire’s Chairs Missing and Mission of Burma’s Vs. for my favorite post-punk LPs. (Entertainment! also dismantled my appreciation for recent groups like Q and Not U and Bloc Party that completely ape its dance-punk edicts.) As a cohesive distillation of their aims and sound, Entertainment! almost discourages a follow-up. Although a great record on its own accord, Solid Gold understandably can’t match its predecessor, suffering from an overly monochromatic palette. “What We All Want,” “Cheeseburger,” and “Outside the Trains Don’t Run on Time” are near equals of classics like “Return the Gift” and “5.45,” but the album lacks sustained brilliance. The prospect of Gang of Four’s slow descent into dance-punk with the emphasis heavy on the dance on Songs of the Free and Hard concerns me, but I’ve let the blurred screen capture on the cover of their third LP stare at me long enough.

Verdict: With original bassist Dave Allen departing for Shriekback, Gang of Four loses some of its rhythmic ingenuity. Replacement Sara Lee is capable, but lacks the signature touches that Allen brought to the first two LPs. Her background vocals are a bigger concern—their presence on “Call Me Up” and the single “I Love a Man in Uniform” may increase the group’s commercial appeal, but take away from the bite of King’s vocals and start the LP on a weak note. Thankfully, “We Live as We Dream, Alone,” “It’s Not Enough,” and “Life! It’s a Shame” close side A with a better combination of this new appeal and their old edge and “I Will Be a Good Boy” and “The History of the World” follow suit on side B. Yet the final two songs, “Muscle for Brains” and the near ballad “Of the Instant,” can’t keep up. (Typing out all of the album’s song titles is an amusing primer for their black-humored Marxism.)

Gang of Four’s nadir arrived with Hard—an album I won’t allow myself to purchase, even as my morbid curiosity grows—when drummer Hugo Burnham left and was replaced by a drum machine. Yet Songs of the Free sows the seeds for Hard’s treason. “I Love a Man in Uniform” is too sarcastic to be a pure sell-out single—“The girls they love to see you shoot”—but its pre-banning success encouraged the group to follow that blueprint, not the reenergized post-punk of “We Live as We Dream, Alone.” Songs of the Free takes one important step forward by losing the dry production of Solid Gold, but takes two steps backwards with its pop tropes and weaker bass lines.

|

36. Prefab Sprout - Two Wheels Good - Epic, 1985

Why I Bought It: I saw Two Wheels Good (more widely known by its British name, Steve McQueen) in the dollar bin at Stereo Jack’s Records in Cambridge and vaguely recalled the band name, but I wasn’t buying enough to hit their $10 minimum purchase level for credit cards and only had enough cash to buy the soundtrack to This Is Spinal Tap and Rex’s self-titled debut. When I later learned that it’s a highly acclaimed recipient of a recent 2CD reissue, I made a mental note to venture back over there with a dollar and change in hand to pick it up. (Naturally, I ended up finding the Cocteau Twins’ Blue Bell Knoll and had to charge the purchase.)

Verdict: Due largely to Thomas Dolby’s mid-’80s production values, Two Wheels Good sounds more adult-contemporary pop than anticipated. The songs themselves, particularly closer “When the Angels,” occasionally transcend this sheen, but I found myself losing focus on what singer/songwriter Paddy McAloon is crooning about. Glancing over the lyrics on a Prefab Sprout fan site makes me want to give it another shot, but ironically—given the vinyl fetishism inherent to this project—it also makes me want to hear the acoustic bonus disc from the CD reissue.

37. Roxy Music - Stranded - ATCO, 1974

Why I Bought It: With all apologies to Stranded’s Playboy Playmate cover model Marilyn Cole, Brian Eno’s early solo work acted as my gateway to his previous band’s catalog, not Brian Ferry’s then-girlfriend. I included For Your Pleasure and Roxy Music in the last round of iPod Chicanery and the strength of those LPs prompted me to pick up Stranded at Mystery Train in Gloucester a few months back.

Verdict: Stranded was the first post-Eno Roxy Music LP, but it’s not lacking inspiration. The up-tempo single “Street Life,” the dramatic, multilingual “A Song for Europe,” and the dynamic “Mother of Pearl” are the clear highlights, but side B is consistently great. There’s a bit of drag on side A after “Street Life”—none of the other songs on that side match its energy—but I imagine that my pacing concerns will evaporate with a few more listens. Bryan Ferry’s croon carries a few of these songs, especially “A Song for Europe,” which whets my appetite for his 1985 solo LP Boys and Girls which awaits in the queue.

38. Stars of the Lid - Avec Laudenum - Kranky, 1999

Why I Bought It: After jumping in headfirst with last year’s excellent And Their Refinement of the Decline, I’ve been working my way backwards through Stars of the Lid’s catalog of ambient classical compositions. 2001’s 3LP epic The Tired Sounds of Stars of the Lid has lingered near my turntable since their astounding performance at the Museum of Fine Arts back in May, but I’ve had my eyes on the vinyl pressing of Avec Laudenum since Record Store Day. The closing of Newbury Comics’ Government Center location prompted a 50% off coupon for vinyl, which I was all too happy to use on Avec Laudenum. (There will soon be a new location in Quincy Market, one that hopefully rivals the Harvard Square and Newbury Street stores in focus and stock.) It will take longer for me to track down SOTL’s earlier LPs, since they’re no longer in print and fetching a premium on eBay, but nothing I’ve heard so far has discouraged me from the pursuit.

Verdict: Avec Laudenum sounds stripped-down in comparison to the two triple LPs that followed it, relying on arcing drones and drifting guitar chords in lieu of strings and brass. Yet this simplicity never seems lacking. Wiltzie and McBride utilize this sonic palette with the utmost subtlety on “Dust Breeding (1.316)+” and “I Will Surround You,” making it nearly impossible to extract particular elements from the flowing warmth of their drone symphonies. In the three-part “The Atomium,” the increasing presence of the guitars signals the concluding swell of the third section and then quickly vanishes, as if the ascent never occurred. When focusing on Stars of the Lid’s reverse artistic progression, it’s tempting to view Avec Laudenum’s soothing minimalism as an appetizer for grander ambience of Tired Sound of Stars of the Lid and And Their Refinement of the Decline. But Avec Laudenum, a five-song LP that comes across as two distinct, ponderous movements, deserves a better fate than to be considered a warm-up lap.

39. Pat Metheny - 80/81 - ECM, 1981

Why I Bought It: Pat Metheny’s involvement in Steve Reich’s Electric Counterpoint and Ornette Coleman’s Song X prodded me to pick up a dollar copy of 80/81, although I left behind a good percentage of his late 1970s and early 1980s releases. While I can sign off on a Metheny album with prominent involvement from Charlie Haden and Jack DeJohnette, my hesitation over his folk-jazz fusion compositions won’t go away until I actually hear one of his records, not a collaboration with a respected peer. 80/81 doesn’t quite qualify as that record, but at least most of these are his compositions.

Verdict: The first minute of “Two Folk Songs” was rather unnerving, as Metheny’s acoustic guitar drives a mid-tempo folk-jazz hybrid into disturbingly light terrain. As the song progressed, however, Jack DeJohnette pummeled away my doubts. His forceful drumming keeps side A from losing focus and pushes Metheny’s acoustic guitar to the background, at least until Metheny gains enough steam to compete. Sides B and C switch to more traditional, less folk-influenced post-bop, including a version of Ornette Coleman’s “Turnaround” from his 1959 LP Tomorrow Is the Question. Tenor saxophonists Dewey Redman and Mike Brecker steal Metheny’s thunder on the lengthy “Open,” spiraling their dueling leads upward in a cacophonous riot as Metheny’s ascending notes only serve as a distraction. Side D returns to the folk-jazz blend of side A, but DeJohnette isn’t nearly as thunderous on these comparatively laid-back tracks. “Every Day (I Thank You)” and “Goin’ Ahead” give Metheny’s layered guitar tracks center stage, but lack the energy of the previous three sides.

80/81 essentially succeeds in spite of Metheny, since the contributing players give far more spirited performances. It’s not difficult to see his approach for this record—bring in acclaimed jazz musicians, do one LP of folk-jazz fusion to demonstrate his particular take on the genre, do one LP of post-bop to lure in the purists and prove his mettle in a more traditional context. Yet 80/81 doesn’t sell me on Metheny’s own compositions when they’re highlighted in the mix (side D), so an album I largely enjoy ultimately does nothing to encourage me to check out Metheny’s personal discography.

40. Bullet Lavolta - The Gift - Taang!, 1989

Why I Bought It: Future Chavez guitarist and Joy Ride screenwriter Clay Tarver started out in the Boston-based Bullet Lavolta, so I was more than willing to grab their debut LP for a dollar. Grabbing it, sure; listening to it, no. The Gift has been lurking in my record collection since I grabbed it (along with a few Volcano Suns LPs and a few less noteworthy albums) at a record fair in Champaign.

Verdict: Whereas Chavez’s riff-driven indie rock had hints of traditional hard rock but never succumbed to the genre’s vices, Bullet Lavolta are neck deep in hard rock bluster. Whether it’s because this material hasn’t aged well, it lacks the visceral jolt of the live setting, or my taste for throttling hard rock doesn’t meet the dosage, The Gift simply doesn’t hit squarely. Tarver and Ken Chambers attempt to find the midpoint between the breakneck pace of 1980s hardcore and the righteous shredding of early Van Halen on tracks like “X Fire,” “Sneer,” “The Gift,” and “Trapdoor,” but never sound as inspired as their source material. Vocalist Yukki Gipe wails and sneers on most tracks, but on “Birth of Death” tries to appropriate the guttural incantations of death metal with curious results, not exactly the intended effect. A reviewer on Amazon writes that if Bullet Lavolta existed in 1994 instead of 1989, they would have been a huge act in the midst of the alternative revolution, but I’ll take that prompt a different way. If Bullet Lavolta existed in 1994 instead of 1989, the weaker tendencies in their sound—the hard rock bluster, in short—would have been antithetical to the times and they likely would have been a more appealing band. Thankfully, Chavez’s mid 1990s existence saves me from worrying too much about Clay Tarver’s squandered potential.

|

|