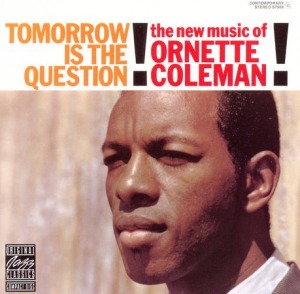

3. Ornette Coleman – Tomorrow Is the Question! LP – Contemporary, 1959 – $15 (RRRecords, 1/7)

I decided at the beginning of this year that the biggest remaining hurdle for my appreciation of jazz (don’t worry, I cringed typing that phrase just as much as you cringed reading it) is the nature of my listening. Instead of dabbling with a wide variety of performers and styles, I’ve opted to focus my efforts on a few key musicians I already know I like. Why I hadn’t done this earlier is beyond me—I can’t imagine thinking “I like 1990s DC rock, so I’m going to buy one album from each band and not worry about following up secondary material from favorites like Jawbox or Shudder to Think.” Such a process ignores understanding how an artist or band changes from album to album.

Ornette Coleman’s third album, The Shape of Jazz to Come, is one of the jazz albums that truly clicked for me on first listen, so it made sense to follow him down the rabbit hole. Tomorrow Is the Question! is Coleman’s second LP, trimming down his debut Something Else!!!! in both members and exclamation points. Gone is contractually obligated pianist Walter Norris, a notable departure of the chord foundation for Coleman’s trade-offs with Don Cherry’s cornet. The rhythm section temporarily dropped drummer Billy Higgins for Shelly Manne (who later appeared on Tom Waits’ Small Change and Foreign Affairs) and featured Percy Heath on bass for side A and Red Mitchell for side B.

These line-up changes underscore what I expected from Tomorrow Is the Question!: it’s a much more traditional album than The Shape of Jazz to Come. Traditional doesn’t necessarily mean bad—there are some lovely compositions on side A and the bright, optimistic mood is infectious—but it’s not as exciting as Coleman’s later works. Coleman and Cherry frequently hint at the free-jazz structures of Shape with their racing interactions, most notably on album highlight “Endless,” but the rhythm section, especially on side A, constricts this freedom. The liner notes mention Manne’s excitement to play without the usual boundaries, but he might have needed a few more albums to fully adapt to this style. There’s no other way to put it: the lack of Higgins and future Coleman standby Charlie Haden on bass is noticeable. I want songs to change course more often, to threaten to come completely apart.

Surely this line works its way into every review of the album given its title, but the most interesting aspects of Tomorrow Is the Question! are those that point to Ornette Coleman’s future recordings. It makes perfect sense that Coleman would progress somewhat gradually—if only two warm-up albums even qualify as gradual—into the free-jazz of The Shape of Jazz to Come. Perhaps the most astonishing fact is that Tomorrow and Shape were recorded two months apart in 1959 and released that same year. How many rock groups release multiple albums in the same year (Robert Pollard, sure) and display marked change from one to the next? (There goes Pollard’s furious hand-waving.) I’m certainly interested in seeing whether Coleman kept evolving at such a frantic pace.

4. Ornette Coleman – Science Fiction LP – Columbia, 1972 – $9 (RRRecords, 1/7)

I paired Tomorrow Is the Question! with Ornette Coleman’s 1972 LP Science Fiction in part to marvel at the expected juxtaposition. Unlike Tomorrow, which I correctly assumed would be a more traditional precursor to The Shape of Jazz to Come, I had no specific ideas of what Science Fiction would offer. Between the hazy, spooky cover art and the decidedly out-there album title, Science Fiction could’ve blasted Coleman off to Sun Ra’s lost planet of space-jazz, taken root in Miles Davis’ jazz-fusion, or found its home with Herbie Hancock’s jazz-funk. I wouldn’t have been surprised by any of these outcomes, yet none of them is remotely accurate.

A look at the personnel would’ve grounded my expectations. Yes, two songs feature vocals from Indian-born singer Asha Puthuli and one features spoken word from poet David Henderson, but regular Coleman contributors like Don Cherry, bassist Charlie Haden, and drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins appear on every track. Science Fiction is never too far from the free-jazz I’m used to hearing from Coleman, but it’s how specific songs and performers stand apart from this foundation that’s intoxicatingly great.

Asha Puthuli’s soulful vocals on “What Reason Could I Give” and “All My Life” are superb. Her voice intertwines with Coleman and the other horns on each song, pulling off the trick marvelously on “All My Life.” Billy Higgins sounds like a man possessed drumming on “Civilization Day.” Charlie Haden’s jaw-dropping solos in “Street Woman” and “Law Years” find tones and textures beyond the usual fingerboard workouts, sounding almost like drones during the former song. Poet David Henderson’s contribution to the title track couples with swarming horns and a baby crying for a profoundly bizarre listening experience. “Rock the Clock” adds texture from Coleman’s violin and Dewey Redman’s musette, which I assume is what sounds like a wheezing electric organ. “The Jungle Is a Skyscraper” lets Coleman, trumpeter Bobby Bradford, and tenor saxophonist Redman take center stage with their solos. There simply isn’t a song on Science Fiction that fails to grab my attention.

Science Fiction is an album I’ll need to spend more time with in order to properly digest. My lone critique of it now is that because of the shifting line-ups, it feels scattershot from song to song. I could have easily done with an album of Asha Puthuli vocals, an album of crazed solos from Billy Higgins and Charlie Haden, or an album of tripled solos from Coleman, Dewey Redman, and Bobby Bradford. Getting all three, in addition to the usually sparkling contributions from Don Cherry and the bizarre poetry of the title track, is a blessing and a curse. Ten listens down the line, perhaps it’s more of one than the other.

|