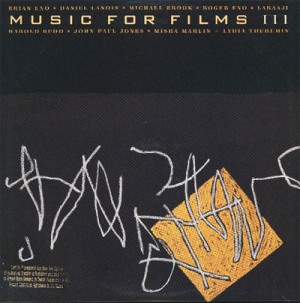

Brian Eno, et al – Music for Films III LP – Opal, 1988 – $4 (10/15 Reckless Records, Broadway Avenue)

In my review of David Sheppard’s On Some Faraway Beach: The Life and Times of Brian Eno, I noted the drop in coverage depth starting in the mid 1980s. Prioritizing his output in the 1970s and early 1980s—specifically Roxy Music, No Pussyfooting, his first four solo albums, Discreet Music, the Ambient series, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, David Bowie’s Berlin trilogy, and Talking Heads’ Fear of Music and Remain in Light—dictates that you’ll read more about albums you’ve likely heard instead of those you haven’t. This situation makes perfect sense. Those are touchstone recordings. Comparatively few people would buy a book emphasizing Eno’s generative art experiments, Nerve Net, collaboration with John Cale on Wrong Way Up, and production duties for James and Coldplay. Yet the unfamiliar terrain of Eno’s late ’80s, ’90s, and 2000s output would have benefitted from a clearer guide. Unlike the 1970s, when it seemed Eno could do no wrong, Sheppard’s speedy run-through (and occasional dismissal) of Eno’s later records indicates inconsistent and frequently unrewarding results. I cite Wrong Way Up and Nerve Net because those are the only two albums I was encouraged to track down. Certainly that can’t be it, right?

My standard “leap before you look” move would be to do a deep dive into the back nine of Eno’s catalog, to become that clear guide I wished for, but I’ve been warned by Sheppard and I will heed that warning. The only three post-1985 Eno albums I’ve heard are 1988’s Music for Films III, 2008’s Everything That Happens Will Happen Today with David Byrne, and 2010’s Small Craft on a Milk Sea with Jon Hopkins and Leo Abrahams (an album Dusted just eviscerated). A conservative estimate of true solo albums and major collaborations puts an additional twenty albums between 1988 and 2008. Yikes. If the sheer number isn’t enough to dissuade you from a deep dive, perhaps the lagging sonics of Music for Films III will do the trick.

I didn’t approach Music for Films III with high expectations. The first Music for Films volume is the rare ’70s Eno LP that underwhelms, since too many of the short, incidental pieces sound inconsequential without the foregrounds of their intended context. Its first sequel came in 1983 as part of the Working Backwards box set, but Music for Films II was mostly a dry run for the superior Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks, containing a few of its tracks and introducing the trio of Brian Eno, Roger Eno, and Daniel Lanois. Music for Films III comes five years later with a change of address—Eno left the sputtering EG label and began his own Warner imprint called Opal. For Opal and Music for Films III, Eno brings in some familiar names: Daniel Lanois, Roger Eno, Harold Budd (from Ambient 2 and The Pearl), and Laraaji (the sole performer of Ambient 3). He supplements them with Michael Brook, Misha Mahlin and Lydia Theremin, and Led Zeppelin’s own John Paul Jones.

A collaboration-heavy Eno album should be no surprise, but Music for Films III is more compilation than collaboration. Of the thirteen tracks on the original vinyl pressing, Eno goes solo on two, collaborates on three, produces three, mixes one, and abstains from involvement on the final four. The results, predictably, are scattershot. Unpredictably, the Enos fare the poorest. Brian’s “Saint Tom” and “Theme from ‘Creation’” suffer from dated synth palettes. Roger’s maudlin “Quixote” would best score a scene of a daytime soap opera in which a main character is exploring a cave. The late-night piano on Roger’s “Fleeting Smile” feels too familiar. Laraaji has the biggest gap in quality, with the modulated vocals of “Zaragoza” sounding thoroughly out of place in a bad way, while the untreated thumb piano on “Kalimba” (heard in the background of “Zaragoza”) stands out with its welcome simplicity. The spooky theremin on Misha Mahlin and Lydia Theremin’s “For Her Atoms” is too identifiable as such, lending an overt ’50s sci-fi air. Harold Budd brings out his usual blurred, new age piano tricks for “Balthus Bemused” with diminishing returns.

Music for Films III isn’t a total wash. Daniel Lanois acquits himself well in his three collaborations with Brian Eno. “Tension Block” is an appropriate name for a dense, bass-driven exploration of Middle Eastern percussion. “White Mustang” is an unnerving callback to Apollo, whereas “Sirens” takes that feeling and shifts it underground. A few contributors also excel. The echoing guitar lines of Michael Brook’s “Err” could stretch out over canyons. The biggest surprise is actually John Paul Jones’ “Four-Minute Warning,” a sound collage of horns that snowballs into cacophony. Did I overlook Led Zeppelin’s free-jazz album?

Beyond the mish-mash of styles and the confounding mix of collaboration and compilation, the biggest problem with Music for Films III is its specificity. Let me explain. The original Music for Films let me down because too many of the incidental pieces weren’t immediately evocative. But for the specific purpose of making music for use in imaginary films, emphasis on the plural, that makes sense. Limiting the contexts for a given piece ultimately limits its utility, and this series is all about utility. Evoking a very particular scene, like the daytime soap opera cave exploration in Roger Eno’s “Quixote,” limits a song’s potential application. It’s not the presence of poor tracks on Music for Films III that lessens my enthusiasm for the twenty years of unexplored Eno albums, since those can be written off as failed experiments from an artist prone to experimentation. It’s the idea that the model is failing that’s truly disconcerting. If I learned anything from On Some Faraway Beach, it’s that Brian Eno loves his models.

|